Securing a sustainable supply chain: lessons from CSR research

- Tue Oct 13 16:04:00 UTC 2015

- Stewart Rassier

A company’s corporate citizenship impact extends beyond its headquarters. To address environmental, social, and governance issues effectively, CSR professionals today must look beyond their own operations and deep into their supply chain. How and where are materials sourced? How are the components of products developed? What are the environmental and human rights ramifications of those processes? Issues as serious as child labor, conflict minerals, and climate change can only be effectively tackled when a company’s commitments to corporate citizenship and reporting are adopted by their suppliers and partners.

A company’s corporate citizenship impact extends beyond its headquarters. To address environmental, social, and governance issues effectively, CSR professionals today must look beyond their own operations and deep into their supply chain. How and where are materials sourced? How are the components of products developed? What are the environmental and human rights ramifications of those processes? Issues as serious as child labor, conflict minerals, and climate change can only be effectively tackled when a company’s commitments to corporate citizenship and reporting are adopted by their suppliers and partners.

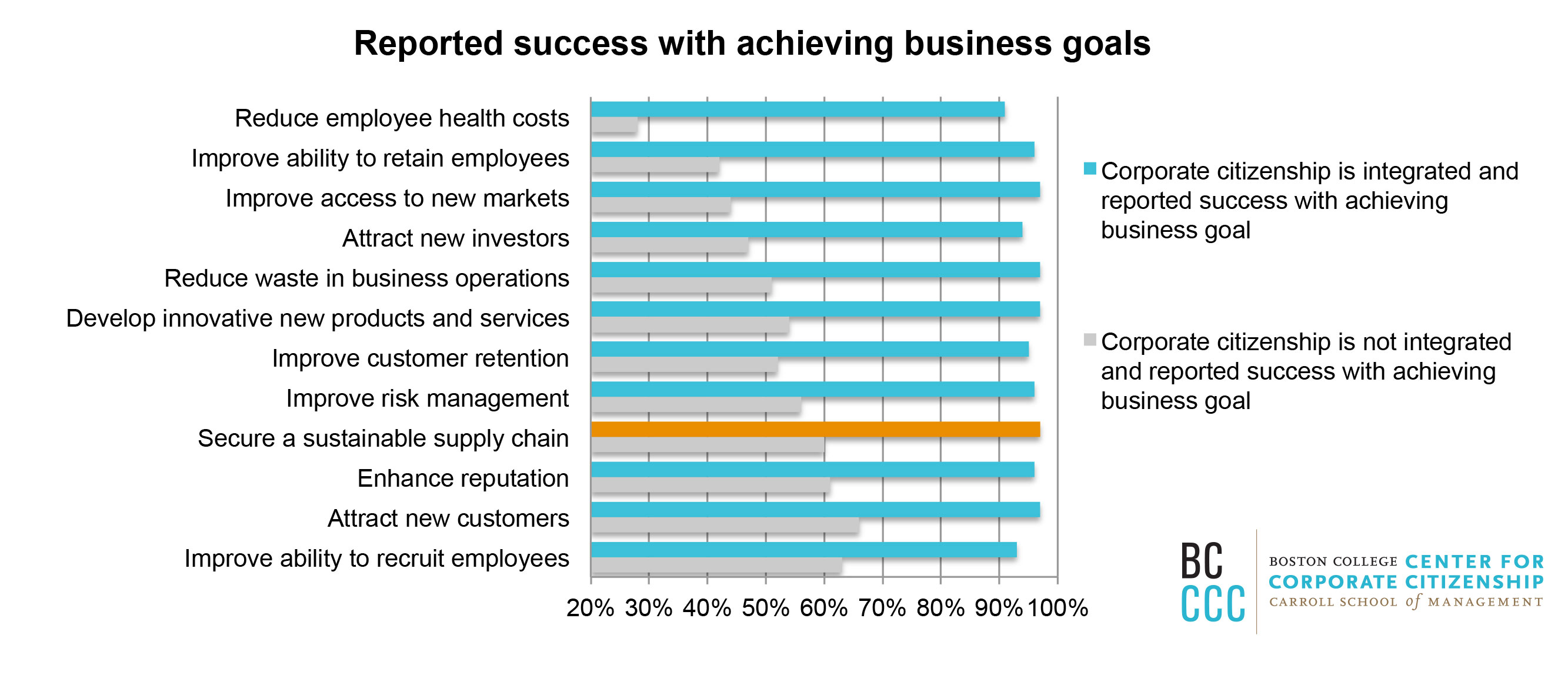

A clear understanding of expectations and a shared commitment can offer business as well as social value to companies and their suppliers both—and corporate citizenship professionals have an important part to play in brokering these relationships. According to the Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship's 2014 State of Corporate Citizenship study, more than 90 percent of executive respondents reported success in securing a sustainable supply chain when corporate citizenship activities were integrated with business strategy, compared to only 60 percent of respondents who reported success when they were not (see below).

When a company’s environmental, social, and governance commitments are not upheld by its suppliers, there can be serious consequences. Research finds that consumers are likely to hold a firm responsible for unsustainable activity regardless of where it occurs within the supply chain. A 2014 study finds that, while the severity of the incident increases backlash, the relationship the supplier has to the firm (direct vs. indirect) and the importance of the supplied product in no way mediates consumer anger.[1] That means that the behaviors of even a supplier that makes a negligible part of a product could pose a serious threat to your company reputation and profit.

The benefits of collaboration

Those companies that do work with their suppliers and partners to manage their environmental and social impacts can achieve greater financial performance in the long term. A 2011 study found that long-term profitability was directly related to greenhouse gas emissions, and that that affect was significantly driven by those released from suppliers.[2]

By collaborating with suppliers, companies can manage performance across the triple bottom line, especially in certain industries. A 2008 study found that manufacturing companies that proactively engaged in a joint planning and decision-making process with suppliers were not only able to decrease their supplier’s environmental impacts, but also increased the quality, delivery, and flexibility of their manufacturing processes.[3]

Some benefits of supplier collaboration occur across industries, and many of these benefits are directly related to corporate citizenship. A 2015 study found that a company’s commitment to sustainability in its purchasing and supply chain functions led to greater collaboration both within and outside of the company.[4] The increased collaboration with its external partners led to greater corporate citizenship performance and cost containment.[5]

Tools, programs, processes

Companies seeking to reap the benefits of greater collaboration should assess the tools, programs, and processes it uses to manage both its corporate citizenship initiatives and its supplier management efforts. Are the needs and impacts of suppliers considered during materiality assessments? Do suppliers receive codes of conduct and/or training to set expectations related to corporate citizenship performance? Are the appropriate frameworks in place to measure and manage supplier performance? Formal environmental management systems, for example, can provide the necessary insights and methods to better evaluate and regulate supplier behavior. A 2011 study found that ISO 14001 certified companies were 40 percent more likely to evaluate the environmental performance of their suppliers, and 50 percent more likely to require the adoption of specific environmental practices.[6]

To develop and implement these processes and procedures, corporate citizenship professionals need management support. A 2012 study found that the adoption of green supply chain processes in B2B markets was dependent upon top management support and trust in the supplier.[7] In B2C markets—where adoption of green supply chain processes is greater—implementation is driven often by by customer expectations and the risk of negative media attention.

Center research suggests that executives understand the value of a sustainable supply chain. In the 2014 State of Corporate Citizenship, 73 percent of executive respondents reported that they considered supply chain partners when developing corporate citizenship efforts, a 15 percent increase from the 2012 study. Also, in the 2014 report, nearly 80 percent listed securing a sustainable supply chain as a key business goal.

These positive executive perspectives underscore the research: Corporate citizenship efforts must consider and incorporate the supply chain in order to deliver maximum business and social returns.

[1] Hartmann, J., & Moeller, S. (2014). Chain liability in multitier supply chains? Responsibility attributions for unsustainable supplier behavior. Journal of Operations Management, 32 (5), 281-294.

[2] Demas, M.D. & Nairn-Birch, N. (2011). Is the tail wagging the dog? An empirical analysis of corporate carbon footprints and financial performace. (Working Paper No. 6). Retrieved from Institute of Environment and Sustainaiblily, UCLA website: http://www.ioe.ucla.edu/perch/resources/2010-delmas-nairn-tail-wagging-dog.pdf

[3] Klassen, R.D., & Vachon, S. (2008). Environmental management and manufacturing performance: The role of collaboration in the supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, 111, 299-315.

[4] Brandon-Jones, A., Brandon, Jones, E., Luzzini, D, & Spina, G. (2015). From sustainability commitment to performance: The role of intra-and inter-firm collaborative capabilities in upstream supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, 165, 31-63.

[5] Brandon-Jones, et all. (2015).

[6] Arimura, T.H., Darnall, N., & Katayama, H. (2011). Is ISO14001 a gateway to more advanced voluntary action? The case of green supply chain management. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 61, 170-182.

[7] Brammer, S., Heojmose, S., & Millington, A. (2012). Green supply chain management: The role of trust and top management in B2B and B2C markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 41 (4), 609-620.