In a recent Plato class, I had my students read a dialogue in which Socrates contrasts himself to other leading teachers of his day, a school of intellectuals called sophists who taught rhetoric and other skills that they thought would help to make young men successful. Socrates claims that he knows nothing for certain except “the things of love” (Theages 128b4). I said to the class: “What a peculiar thing this is for Socrates to claim. Can you imagine universities marketing themselves in this way: we teach you absolutely nothing, nothing except things about love.” The students laughed, and then one of them replied, “But isn’t that at least part of what our Jesuit education is about?” Absolutely. The student is right: part of what we want in forming our students is for them—and for faculty and staff, too—to love well.

As a professor of philosophy, I care about the knowledge that is foundational for my field, and I try to prepare both graduate and undergraduate students well in my areas of expertise. We do teach specific knowledge. But what and how any of us choose to teach is not morally or socially neutral. At Boston College (BC), I have engaged in many conversations with fellow faculty where we have intentionally asked and reflected on the following kinds of questions as well: How can teaching help students and future citizens to live in communities that are more just and more loving in seeking out that justice? How in the Core Curriculum do we teach people scientific, sociological, theological, artistic, and historical ways of knowing, both for their own sakes and so that they can better understand the world and their place in it after graduating? How is simply coming to know, to contemplate what is good and beautiful for its own sake, also part of what it means to “know the things of love”?

I am currently teaching a course on Mass Incarceration. The course is composed of graduating seniors who are curious or, in some cases, already passionate about examining our incarceration system more deeply. In both classes, though, there is a shared commitment to seeking what is true and reflecting on how it is meaningful both in and outside of the classroom. I hope that my students will lean into the complexity of philosophical arguments that reflect the complexity of our lived social and ethical realities rather than seeking simple answers. Most of my Mass Incarceration students find our high rate of incarceration, with its unequal treatment of Black and Brown people in our criminal justice system, to be unjust. They long for greater fairness and for more of an emphasis on rehabilitation than punishment. Some wonder whether the entire system ought to be abolished in its current form. At the same time, they also recognize that protecting society from individuals who harm others is important, and they wrestle with how that can best take place. As we read through theories examining our criminal justice system, students also connect this to service work in which they are engaged, and let their experiences inform their evaluation of the theories, and vice versa. For me, this sort of integration of theory and practice is a skill that I hope will, indeed, help them to know better concretely how to work for a more just society after graduation—whether that means working as a prosecutor or defense lawyer, as some have gone onto do, or as reflective citizens who consider these issues as they vote or are politically active.

What has surprised me is how much both teaching my classes and the commitments of other colleagues have also formed me. Twenty-six years ago, I came into BC as a Protestant interested in the Catholic intellectual tradition and already drawn to the liturgy, and through teaching in Core I have not only gained a sense of respect for its value, I also converted and became a Catholic. Through listening to students and fellow faculty and staff over the years, I’ve also become aware of how important a deep spirit of inclusion—inclusiveness of religion, class, sexual orientation, nationality—is for us to really be “catholic” in the sense of “universal.” When I arrived at Boston College, I was not well-versed in post-Holocaust moral theology or philosophy of race. But in the course of conversations with others, I grew in my understanding of what students might need to know in order to live and love well in the world in which we reside. I have been formed to love and appreciate many of the ideas in these texts. A faculty/staff immersion trip to Nicaragua years ago, led by Mission and Ministry, not only had a lasting impact on me in widening my sense of the Americas beyond North America, it also has formed points of connection with students. For example, a recent Presidential Scholar told me about her immersion trip to Costa Rica and was sorting out how it may inform the larger arc of her education, especially in care for marginalized communities.

Part of what we want in forming our students is for them—and for faculty and staff, too—to love well.

Being in dialogue with people of different religious, social, racial, and national backgrounds in our work together hopefully shapes us in how the general ideals of the mission get lived out in practice. Just as is the case with my student who places their classroom theories in dialogue with practice, as educators we also have to revise our own concepts of what a good education looks like as we listen to the experiences of others across differences. We are still not “there” yet, but a Jesuit, Catholic university that wants that mission to be successful needs to be open to the sort of cross pollination between faculty, and between students and faculty, that makes our work more fruitful.

For me, Jesuit, Catholic education does not end in the classroom, quad, or even the dorm room; it extends into the larger community. My colleague in theology, Jim Keenan, S.J., wrote an essay on the idea of Jesuit hospitality in which he argues that in contrast to religious orders who sought to find Christ in the visitor to the monastery, the apostolic nature of the Jesuits means that they are called to go out into the wider community and to seek Christ in the other there. I teach this article at the end of the year in my PULSE class, Personal and Social Responsibility, where students serve 10–12 hours a week at nonprofits and schools in the city of Boston while learning about philosophy and theology. At the end of the year, after they read Keenan’s work, I ask them to reflect on what the difference would be if, instead of going out into the city, they served the same clients at BC. Without exception, the students think the experience would be lacking. First, they find that through service, they learn that they are not lone individuals but are part of a larger community, which they get to know through their time working with community partners. Many express the idea that they learned not only from class but also from these communities beyond the “BC bubble.” Keenan also asks us to reflect on how we can bring that sense of hospitality back to the University itself. So I also ask students to consider, as a year of service ends, who is marginalized within the University community and needs to be brought in, and how many of those same folks have a lot to teach the rest of us about truth, goodness, and justice.

For me, teaching at a Jesuit, Catholic university is not only about teaching a body of knowledge, it is also learning more about the core of what it means to be human. For me, Socrates’s idea that he knows only about love resonates with Ignatius’s claim in the Principle and Foundation of the Spiritual Exercises that we ought not to treat health, wealth, reputation, or other limited goods as though they are the ultimate end; love of God and love of our fellow human beings is the point of all of our labors. While we indeed have further to go in how to live out that ideal, and we do not do so perfectly, that we have this aim at all sets apart Jesuit, Catholic universities. To seek to better understand the “things of love” is indeed a worthy aim.

Marina Berzins McCoy is a professor of philosophy at Boston College and teaches in the Personal and Social Responsibility service learning program (PULSE).

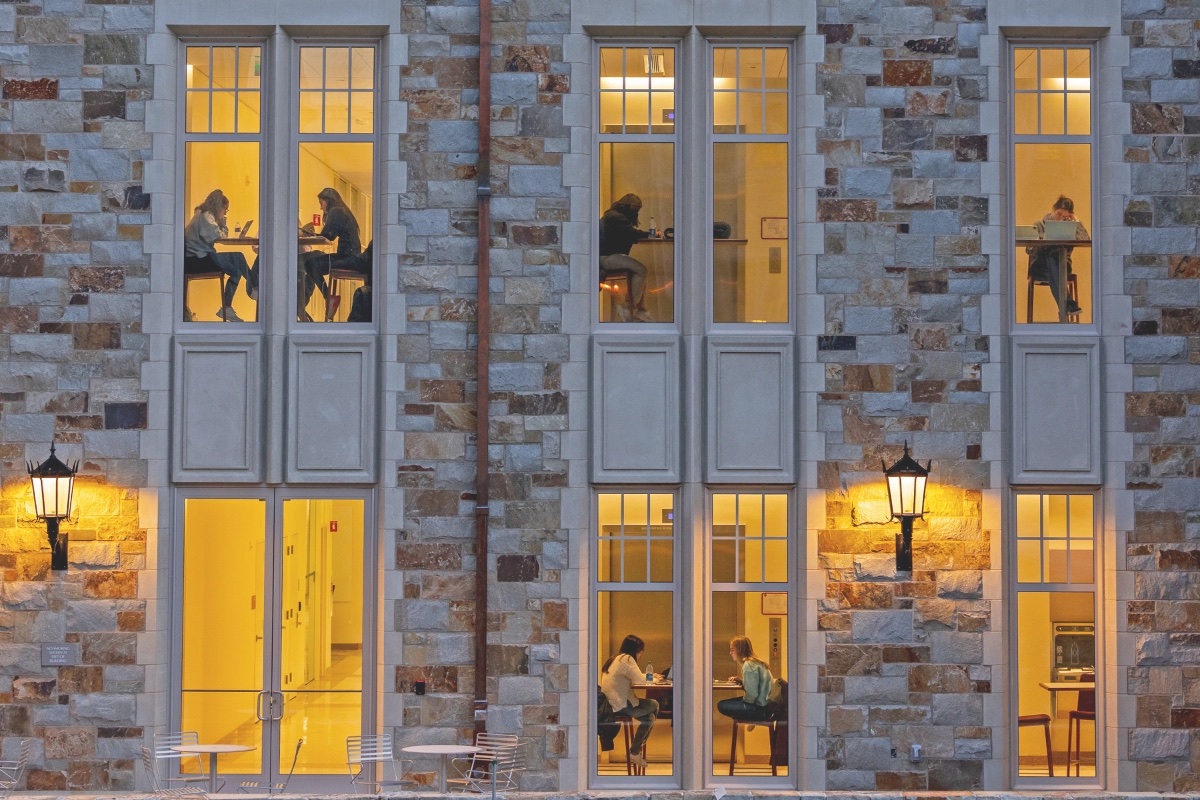

Photo: Students serving others through BC’s transformative PULSE service learning program, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2020. To date, this pioneering initiative has accumulated over 3.2 million hours of service in the community. Photo credits: Courtesy of John Walsh '17, M.B.A. '20, Boston College

To learn more about PULSE, visit: bc.edu/pulse