Recent debates regarding in vitro fertilization (IVF), fetal personhood, and state law have brought infertility and infertility treatments back into the national spotlight. In policy discussions and theological conversations alike, disagreements about the moral status of embryos and the ethical implications of fertility treatments persist. The intractability of these debates makes it difficult to see how we might work toward the kind of social reconciliation that Pope Francis, in his encyclical Fratelli Tutti, named as central to the life of fraternity and social friendship to which the Gospels summon us.

Francis suggested that dialogue can help us find our way out of fragmentation to rediscover our common humanity. He says that “[a]uthentic reconciliation” does not involve avoiding conflict, but instead “is achieved in conflict, resolving it through dialogue and open, honest and patient negotiation” (7.243). An appeal to dialogue may on its face sound unimaginative or cliché—an impractical strategy to begin to address divisive and emotion-laden disagreements in reproductive politics. Yet, Francis’ way of defining dialogue can, I find, challenge and refresh our ways of responding to the realities of our disagreements. He understood dialogue expansively: “Approaching, speaking, listening, looking at, coming to know and understand one another, and to find common ground: all these things are summed up in the one word ‘dialogue’. If we want to encounter and help one another, we have to dialogue” (FT 6.198). For Francis, dialogue wasn’t just about discourse and debate; it is embodied. It involves not only “speaking and listening,” but also “approaching” and “looking at” one another. It strives for knowledge and understanding of the other, and a willingness to recognize what we share in common.

As I reflected on the type of open-ended encounter that Francis seemed to envision here, I was struck by its resemblance to my experiences of conducting qualitative research.1 Between 2020–2023, I interviewed 57 Catholic women who had experience with infertility. While my research aimed to respond to issues emerging in public debates—I wanted to weigh in on the ethical implications of reproductive technologies and scrutinize the social forces that shape moral decision-making related to infertility treatments—the interview process demanded more listening than speaking. It required me to be more receptive and less opinionated. Success, in the context of an interview, was not agreement or persuasion, but understanding. Qualitative methods prioritize the encounter of another person in their complexity, and they demand from the researcher patience, receptivity, and curiosity. In this way, the process of qualitative research can function as a kind of reconciling practice.

As Kathy Charmaz, an expert on a kind of qualitative research called “grounded theory,” argues, the goal of qualitative methods, including interviewing, is to strive “to see this world as our research participants do—from the inside.”2 One of the commitments of grounded theory research is to “preserve our participants’ human dignity even if we question their perspectives or their practices.”3 We do our best to understand participants and their perspectives, to “test our assumptions about the worlds we study,” and “look at their world through their eyes...”4 The partnership forged between researcher and participant in the process of qualitative researchencourages receptivity and understanding, which are crucial to the work of reconciliation. With a commitment to understanding the person right in front of us, it is easier to heed Francis’ caution against clinging to our own preconceived notions in conversation—something that he saw our media environment exacerbating. In a memorable turn of phrase, Francis laments “the media’snoisy potpourri of facts and opinions” as “an obstacle to dialogue” that encourages the person to “cling stubbornly to his or her own ideas, interests and choices, with the excuse that everyone else is wrong” (FT 6.201). “Authentic social dialogue,” by contrast, “involves the ability to respect the other’s point of view and to admit that it may include legitimate convictions and concerns” (FT 6.203).

In my interviews with Catholic women who had experienced infertility, I developed an appreciation for what the theologian and anthropologist Todd Whitmore calls “the mess that is life” in its diversity and its uncertainty.

The work of qualitative research, at least as I experienced it, is not far off from Francis’ vision of dialogue. Both assert the dignity of the person and insist on the importance of conversation that foregrounds openness, listening, and understanding. Francis himself observed that through “interdisciplinary communication” and receptivity to “various angles and different methodologies,” researchers can “become open to a more comprehensive and integral knowledge of reality” (FT 6.204).5 And indeed, the scholarship of several Christian ethicists aptly demonstrates how qualitative research can help theologians hew closer to reality—to truthfulness—in our moral reflection.6

In my interviews with Catholic women who had experienced infertility, I developed an appreciation for what the theologian and anthropologist Todd Whitmore calls “the mess that is life” in its diversity and its uncertainty.7 All the women I interviewed had a connection to Catholicism and experience with infertility, but they differed in many ways—age, country of origin, family size, ethnicity, racial background, political affiliation, profession, faith practices, and more. They had different experiences—of infertility, of miscarriage and reproductive loss, of infertility treatments, of the response of their parishes and their families, of their relationship with God. They had different beliefs—about official Church teaching about the moral status of embryos, about the morality of treatments like IVF, about the role of the Church in society. They made different choices—some went through IVF or artificial insemination; some sought treatment in Catholic clinics that aligned with Church teaching; some unexpectedly conceived; some pursued fostering and adoption; some left the Church and critiqued its emphasis on motherhood; some rethought what counted as “procreative” in their lives; some were still figuring out what their next step was.8

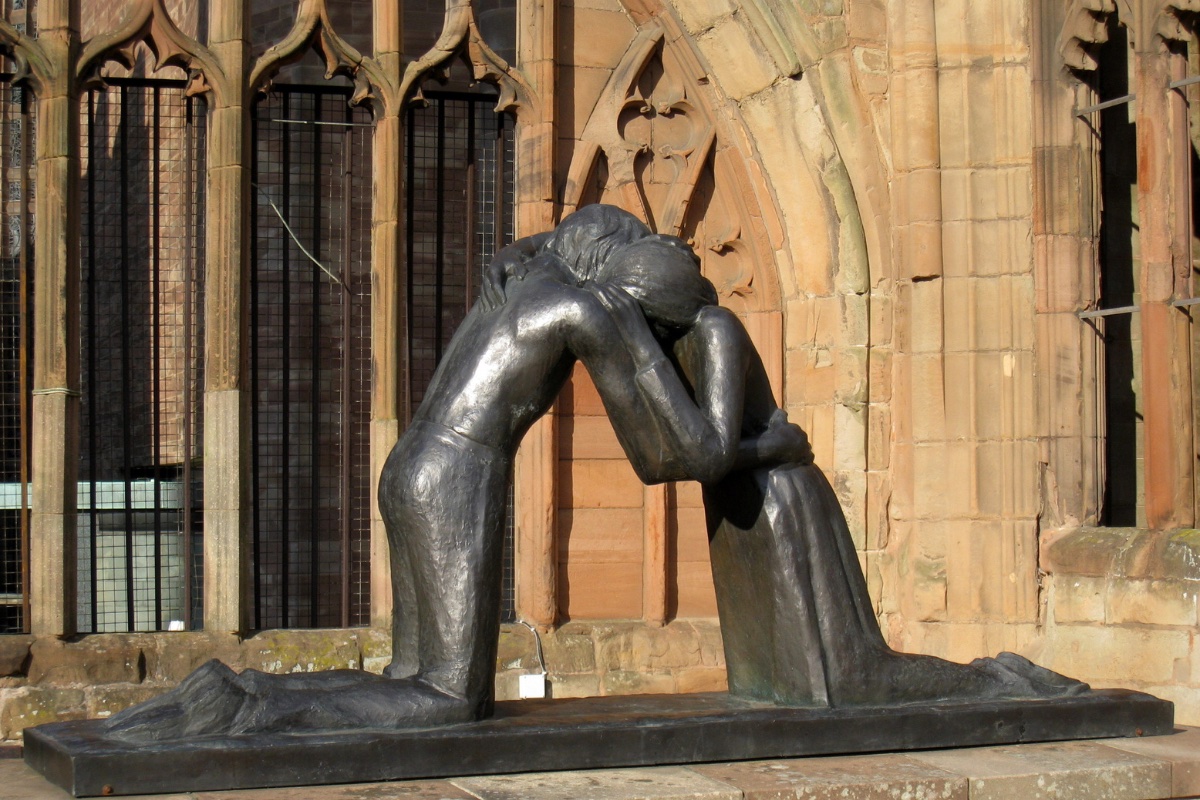

These conversations opened up my research in complex and nuanced ways that I cannot render adequately here. What I can communicate, in the spirit of Francis’ exhortation to find common ground in dialogue with one another, is that each person I interviewed faced a particular expression of a central human challenge we all, in our own way, know well—to reconcile ourselves to our frailty, our ignorance, our finitude. For those who hope to have children, infertility can be an abrupt and unwelcome sign that we lack control. Our very bodies can thwart our deepest desires. For all the advances of modern medicine, we remain finite creatures. Muddling forward is difficult, confusing, and uncertain. It is no wonder we face such trouble discerning as a society what paths lead to the good.

In our strivings for social reconciliation, we do well to seek out opportunities that confront us with the obvious yet overlooked truths of our common humanity, that stretch and strengthen our capacity to encounter the reality of one another. As Pope Francis reminded usin Fratelli Tutti: “Each of us can learn something from others. No one is useless and no one is expendable...What is important is to create processes of encounter, processes that build a people that can accept differences. Let us arm our children with the weapons of dialogue! Let us teach them to fight the good fight of the culture of encounter!” (6.215, 6.217).

Emma McDonald Kennedy, Ph.D. ’23, is assistant professor of Christian ethics at Villanova University.

Illustration: Adobe Stock/OneLineStock

Sources:

- Tricia C. Bruce makes a similar connection, linking synodal listening with social scientific methods, in “Asking to Listen: Engaging Social Scientific Methods as a Listening Practice in Global Catholicism,” Journal of Moral Theology 13, Special Issue 2 (2024): 239–251.

- Kathy Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2006), 14.

- Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory, 19.

- Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory, 19.

- Pope Francis’ Motu Proprio Ad theologiam promovendam from November 1, 2023, makes a similar point about the importance of developing a methodologically diverse, contextual that foregrounds dialogue and expansive engagement.

- See, e.g., Christian Scharen and Aana Marie Vigen, Ethnography as Christian Theology and Ethics (New York, NY: Continuum, 2011); Ada María Isasi-Díaz, La Lucha Continues: Mujerista Theology (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004); Emily Reimer-Barry, Catholic Theology of Marriage in the Era of HIV and AIDS: Marriage for Life (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2015); Jennifer Beste, College Hookup Culture and Christian Ethics: The Lives and Longings of Emerging Adults (Oxford University Press, 2018; and Todd Whitmore, “Holy Deviance: Christianity, Race, and Class in the Opioid Crisis,” Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics 40, no. 1 (2020): 145–162.

- Todd Whitmore, “Bringing the Mess That is Life into Theology: The Representational Task of Ethnography,” Ecclesial Practices 8, no. 2 (2021), 145.

- My point here is neither to imply that these are all morally equivalent choices nor to neglect the relevance of women’s varied social contexts and the related social forces that contribute to shaping the decisions they make––these are important considerations that my dissertation and related research projects take up in detail. My aim in this reflection is to center processes of dialogue and points of commonality relevant to social reconciliation.