“Reconciliation” in our everyday experience suggests the restoration of friendship or harmony between individuals or groups that have been separated from one another by bitter conflict. Biblically, “reconciliation” is used more frequently to describe humanity’s relationship with God. We tend to think of that relationship as an individual experience initiated by a person who repents. Yet, when we turn to the Bible, we find that such individual acts of repentance are notthe primary subject of reconciliation language at all. The most important use of reconciliation describes God’s turning toward a sinful humanity.1 Without practices of justice based on reconciliation and mercy, God’s holy people cannot survive.

TENSIONS BETWEEN BROTHERS: JOSEPH TO JESUS

Genesis has repeated tales of tensions between brothers that culminate in the murderous plan of Joseph’s brothers (Gen 37-50). But thanks to his rise in Pharaoh’s court and wise provisions for impending famine, Joseph not only saves Egypt but his own people as well. The passage’s final words of fraternal reconciliation are, “Even though you intended to do harm to me, God intendedit for good, in order to preserve a numerous people” (Gen 50:20). This story highlights an important facet of reconciliation. It does not “forget” the past hostility or injustice. Joseph had devised elaborate testing of his brothers to prove their change of heart before the great reveal (Gen 42-44). Only then does the story end with Joseph forgiving his brothers.

Numerous Hebrew narratives told the tale of younger sons surpassing privileged elder brothers. But Jesus flips that script in the Prodigal Son parable (Lk 15:11-32). Here family dynamics of Jesus’ Jewish audience is writ large. The younger son has alienated himself from everything Jewish. Left starving among pigs, he remembers the justice of his father’s farm. On the way home, he rehearses a confession that his father’s joy overrides. But the father must still bring his older son into that party, “...brother of yours was dead and has come to life” (v. 32). This is not at a cost to the elder of his relationship with the father. Reconciliation requires changing “hearts” on both sides—acknowledging failures and joyful embrace of the lost. Only then is the family restored.

TO GOD’S EARS: FORGIVENESS AND PRAYER

Similarly, a transformed heart appears in the prayer which Jesus recommends to disciples seeking God’s forgiveness. Luke 11:4 refers to a source of communal tensions, debts owed: “...forgive our sins, for we forgive everyone indebted to us” (Lk 11:4). Matthew’s longer, liturgically adapted version has framed petitions as requests for the realization of God’s will on earth, “...forgive us our debts as we also have forgiven our debtors (Matt 6:10-12). Even when it is described as forgiveness, reconciliation is not merely a private transaction between the individual and God. Reconciliation seeks to establish the holiness of the people of God.

Christians typically open worship by acknowledging sin and asking God for forgiveness. Matthew 5:23-26 contains two sayings of the Lord aimed at reconciliation. First, “...if you remember that your brother has something against you, leave your gift...go first and be reconciled...” (Matt 5:23-24). Jesus warns that one is to be reconciled with the person one has offended before approaching God in the liturgy. This injunction is followed by a separate proverbial wisdom saying (Matt 5:25-26; Lk 12:57-59) to settle disputes before getting into court. Otherwise, a capricious system of justice can land persons in prison, “...until you have paid the last penny.”2 So, courts being courts and prisons being prisons, they cannot deliver the healing reconciliation which Jesus imagines as God’s kingdom coming to Earth.

Reconciliation requires changing “hearts” on both sides—acknowledging failures and joyful embrace of the lost.

FORGIVENESS IS THE RULE

Communal life can be poisoned by resentments. The community is summoned to exemplify forgiveness and reconciliation in the concrete relationships between its members. Jesus offered various exhortations, “If another disciple sins, you must rebuke...if the same person sins seven times a day and turns back...and says ‘I repent,’ you must forgive...” (Lk 17:1-4). Matthew 18:15-22 offered procedural rules for how the community is to address a wayward sinner. Matthew 18:17 incorporates expelling a person who refuses to accept the community’s decision. However, the entire emphasis of this section is not upon excluding sinners, but upon winning them back.

This is followed with the dramatic Parable of the Unforgiving Servant (Matt 18:23-35). Jesus’ parable opens with a servant forgiven a debt greater than the annual budget of Herod’s kingdom. Such a great relief should have changed his heart, but did not. The servant’s refusal to extend forgiveness when another seeks relief for a plausible amount results in his downfall. The king retracts the prior forgiveness. Jesus’ parable provided a warning to Christians that their forgiveness must be modeled after what they have received from God. Thus, it would be wrong to imagine the possibility of “sins being retained” by the community. Quite the contrary, the quest is to seek out, to forgive, to reconcile.

Peeking through the leaves of Paul’s letters are glimpses of situations that required churches to practice reconciliation. Writing from prison, Paul asks a companion in Philippi to help reconcile two women involved in Philippian evangelization efforts (Phil 4:2-3). 2 Cor 2:5-12 speaks to another situation in which Paul himself had been the victim during a disastrous visit. The Church has turned back to its apostle founder. Paul encourages them to forgive the original offender, “...so that he may not be overwhelmed by excessive sorrow” (v. 7).

IN CONCLUSION

Our sampler of biblical witnesses uncovers a multifaceted approach to the human difficulties with forgiveness and reconciliation. Even the legitimate justice of the guilty “paying the penalty” will not elicit a change of heart that will embrace offenders as beloved brothers and sisters. Proverbs 17:14 highlights vigilance: “The beginning of strife is like letting out water; so stop before the quarrel breaks out.” We see in Leviticus 19:18 that, “You should love your neighbor as yourself” rather than harboring “hate in the heart” that seeks revenge.Reconciliation embraces all of the significant dimensions of salvation in the New Testament. The radical conversion and reorientation of one’s life in baptism is carried out in the community of reconciliation. That community is summoned to exemplify forgiveness and reconciliation in the concrete relationships between its members. The community is called to share the destiny of its Lord in undertaking a ministry of reconciliation that is addressed to the whole human community (Col 1:24-29).3

Pheme Perkins is the Joseph Professor of Catholic Spirituality at Boston College, where she teaches Biblical Theology.

Sources:

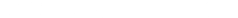

Illustration: The Forgiving Father (1950), by Indian-Australian artist Frank Wesley (1923–2002) powerfully depicts the Parable of the Prodigal Son, capturing the moment the son is welcomed home by his father.

The New Testament on Reconciliation

The vertical dimension of reconciliation is God’s role in reconciling the world to himself. It deals with the restored relationship that exists (at least potentially) between God and human beings, and focuses on what reconciliation reveals about the character and nature of God. The horizontal dimension of reconciliation is how God’s act of reconciliation has created new and life-giving ways for people to be in communion with one another. Finally, the ministerial dimension of reconciliation shows that God’s work continues in the newly founded Church.

The New Testament teaches that reconciliation begins with God. Through the self-giving love of Jesus, culminating with his death on the cross, God has acted to reach out and reconcile the world to himself. The source of reconciliation is God’s compassionate, merciful love, his impetus to make right what has gone wrong through human sin. The restoration of the divine-human relationship also involves the healing of relationships between human beings. Indeed, the authentic appropriation of the vertical dimension of reconciliation requires a commitment to the horizontal dimension, to the healing of the divisions and enmity among peoples. The mark of a person who has truly received God’s mercy and forgiveness is to become more merciful and forgiving in turn. The Christian community is to be the place where reconciliation is both practiced and imaged forth for others to see.

Thomas D. Stegman, S.J. (1963–2023) was professor of New Testament, professor ordinarius, and former dean of the Clough School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College.

This excerpt from “What Does the New Testament Say about Reconciliation?” in Thomas A. Kane (ed.), Healing God’s People: Theological and Pastoral Approaches/A Reconciliation Reader (Paulist, 2013) is reprinted with permission—paulistpress.com.